1982-1990 Comyn Ching Triangle, Seven Dials, Covent Garden, London, WC2.

Refurbishment and new build scheme with Farrells to convert listed seventeenth century buildings for mixed use including shops, offices and 25 flats and house creating a new urban courtyard. The project won a Civic Trust Award in 1985 for the first phase courtyard and houses designed by Gary Young and was recognised as setting the highest standards of design in the context of historic buildings. The courtyard, paved in York Stone, provided new entrances to the offices and flats creating a unique urban space in Central London and increasing the potential value of both retail on the street frontages and the upper floors. Historic fabric and details were retained on both exterior and interiors including over ten original staircases of varying late seventeenth and early eighteenth century designs. New buildings were designed for the corners of the triangular site for mixed uses.

Above mentioned on Wikipedia Page for Farrells

Historic England application for Comyn Ching Triangle listing in 2016

Applications were made to Historic England in 2015 by Sir Terry Farrell and Gary Young for the entire Comyn Ching Triangle to be considered for historic listing. Widely regarded as a significant exemplar of 1980's regeneration, the buildings and urban spaces, now 30 years old, needed further protection from insensitive alterations. Historic England in 2016 confirmed the grade 2 listed status for the entire group. The application for the listing was widely supported by historians, architects, residents and heritage groups including the 20th Century Society. The architectural press reported positively on the success of the landmark listing for an architectural regeneration of the 1980’s which is celebrated as an exemplar.

Photographs of the National Trust visit to Comyn Ching Triangle 30th April 2016

Comyn Ching Triangle description by Gary Young - January 2018

Design inspirations for interiors.

Farrells design inspirations for the new interiors and courtyard for Comyn Ching Triangle were in part the discoveries made during the lengthy recording and planning stages for the restoration of the historic houses. This research found that the existing interiors were representative of a period of rapidly changing design over a few decades in late 17th century. The Comyn Ching Triangle regeneration project during the 1980's was a period when previously dominant ideologies were sufficiently challenged to enable new concepts and ideas to flourish. The energy and talent within Farrell's London studio created ambition for new designs to equal the creativity found in the past. This combination created an unique opportunity for the thoughtful and original approach at Comyn Ching Triangle. Farrells design team had produced innovative and experimental architectural vocabularies for previous projects during the early 1980’s which were creating significant interest among architects. These earlier projects used colour and contemporary materials to articulate and represent both solidity and lightness, referencing context and liberally merging design influences ranging from Art Deco, Memphis, Classical and Pop Culture.

The Comyn Ching Triangle designs clearly benefit from the inherent special context of the place, visible in the original detailing of the historic buildings. The existing Comyn Ching Triangle buildings were first built, then altered and improved, during a dynamic period of change in domestic architecture from the late 17th to early 18th centuries. The existing details provided a deep understanding of the changes which took place during the period of their design and construction. There were wide ranging influences on town house design during this period when the Comyn Ching Triangle was built. The 1666 Great Fire of London resulted in the London Building Acts of 1667, 1707 and 1709 which required brickwork for fire protection in roofs and walls, changing the placement, scale and detail of windows and doors. The 16th century typical town house was also evolving into a residence with status in planned developments. Inigo Jones design for Covent Garden piazza built 1637 was the first planned square in London, followed by Thomas Neale's plan for Seven Dials built 1692. The introduction of developers building houses on the planned streets created trends towards refined details and room layouts, particularly for the principal front and rear rooms which were improved by moving the stair from a central position across the width toward the rear of the house. Along with these functional changes there were wider influences from Europe with architects designing interiors of churches and state rooms with new ornament and detail. The existing Comyn Ching Triangle houses, built during this critical period which shaped London, had retained identifiable architectural elements spanning across a revolution in design over the few decades of the late 17th and early 18th century.

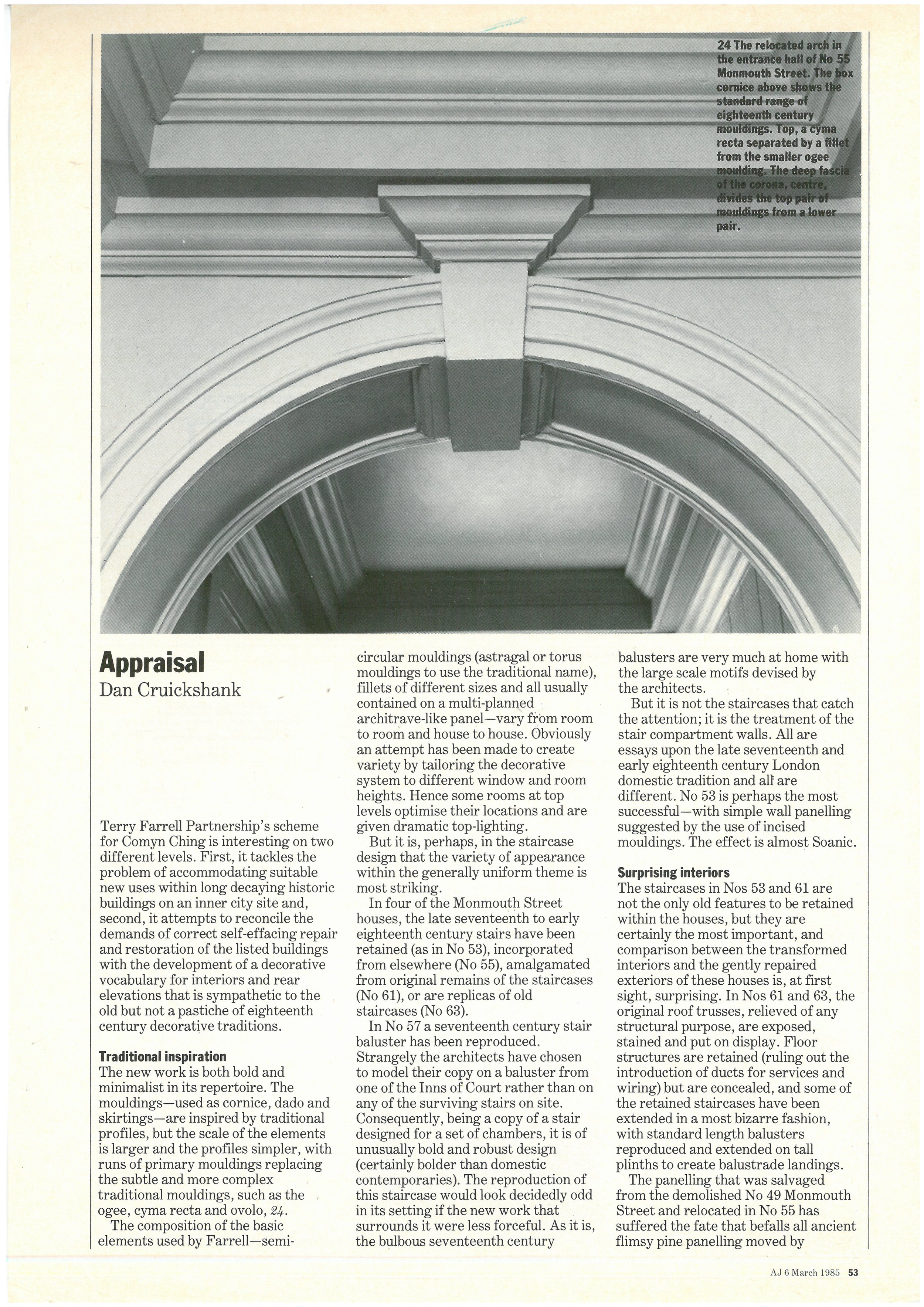

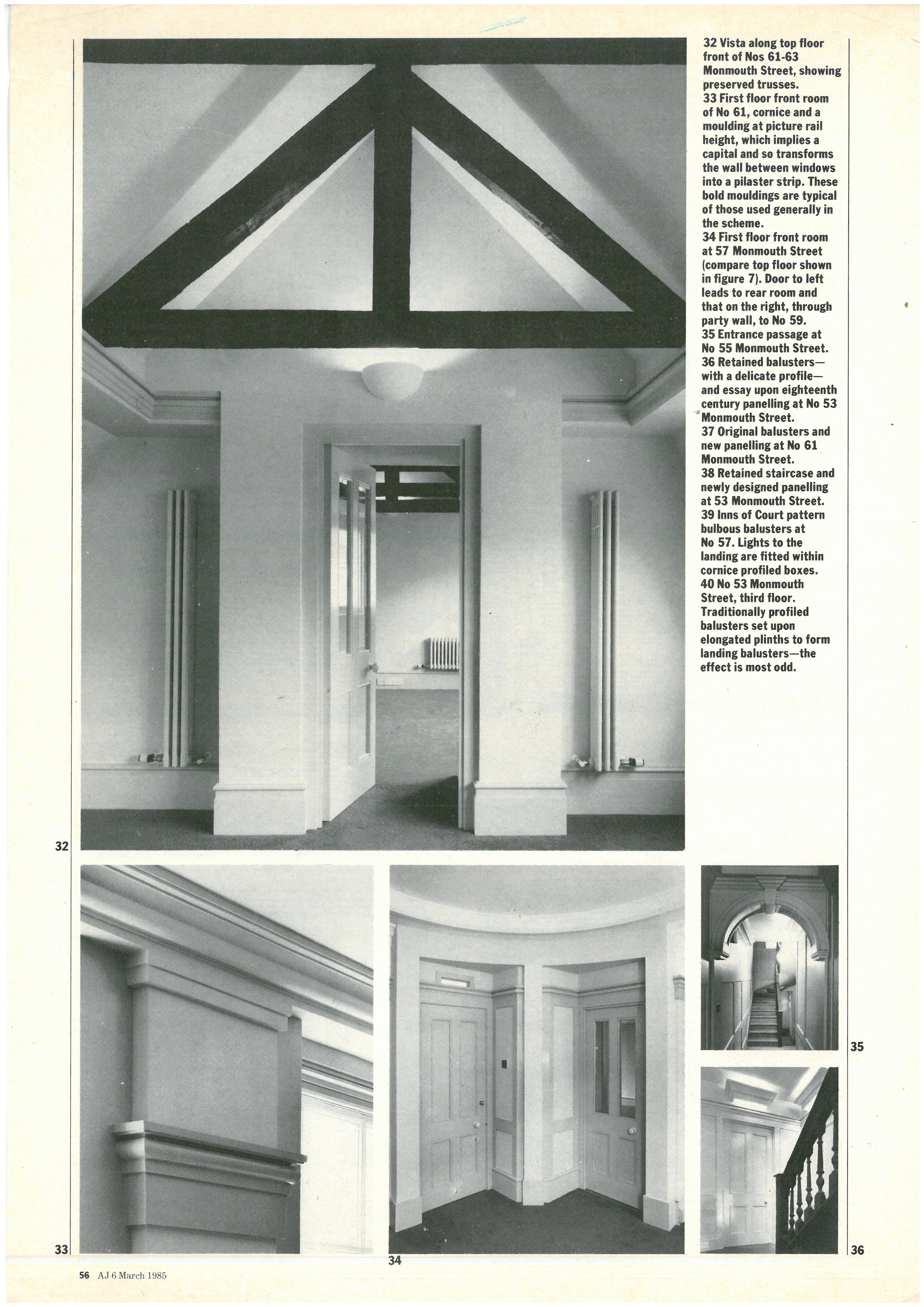

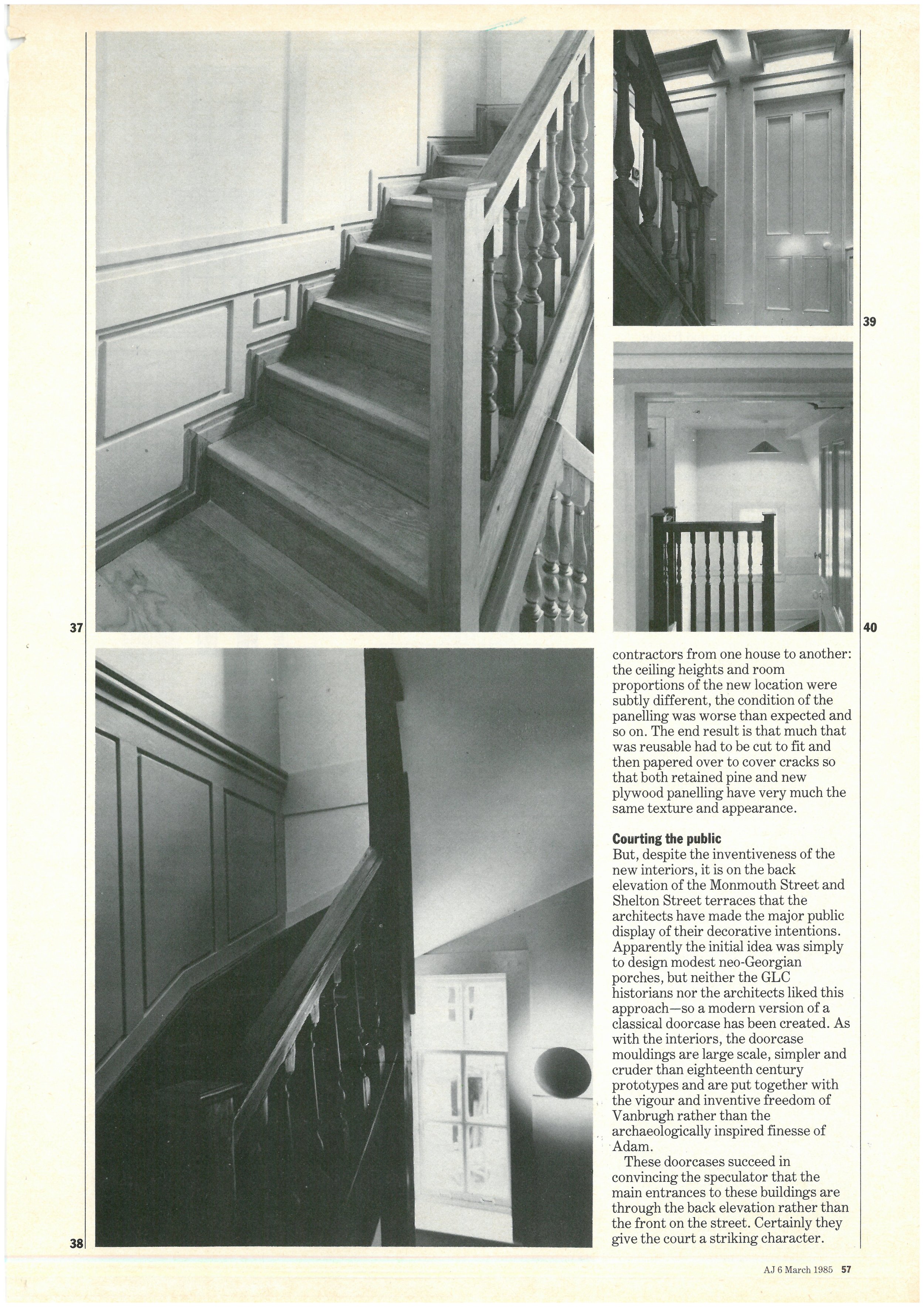

The new interior designs for Comyn Ching Triangle were grounded by an understanding of historical detail, with careful observation and survey of the surviving timber moulded panels, doors, shopfronts and staircases. These existing architectural elements were faithfully recorded to be expertly restored by craftsmen. Several distinctive details had been identified from the few remaining late 17th century houses. These interiors had simpler and more exaggerated shapes in stair balusters and mouldings compared to more refined mouldings introduced in the early 18th century houses. The interior details had clearly evolved in successive restyles over a few decades at the turn of century, pointing to the eventual direction of a refined 18th and early 19th century Georgian style. Examples in Comyn Ching Triangle were identified and preserved with the variety able to show the rapid transformation in London domestic architecture. The design team's enthusiasm grew with the task, with no wish to stop at preservation. Several of the 17 houses were left without remaining mouldings or staircases and these provided a blank canvas. Supported by the GLC Historic building division, who shared the depth of understanding of the interiors on neighbouring houses, ambitious designs for new contemporary interiors were produced with a family of mouldings, innovative in form and detail.

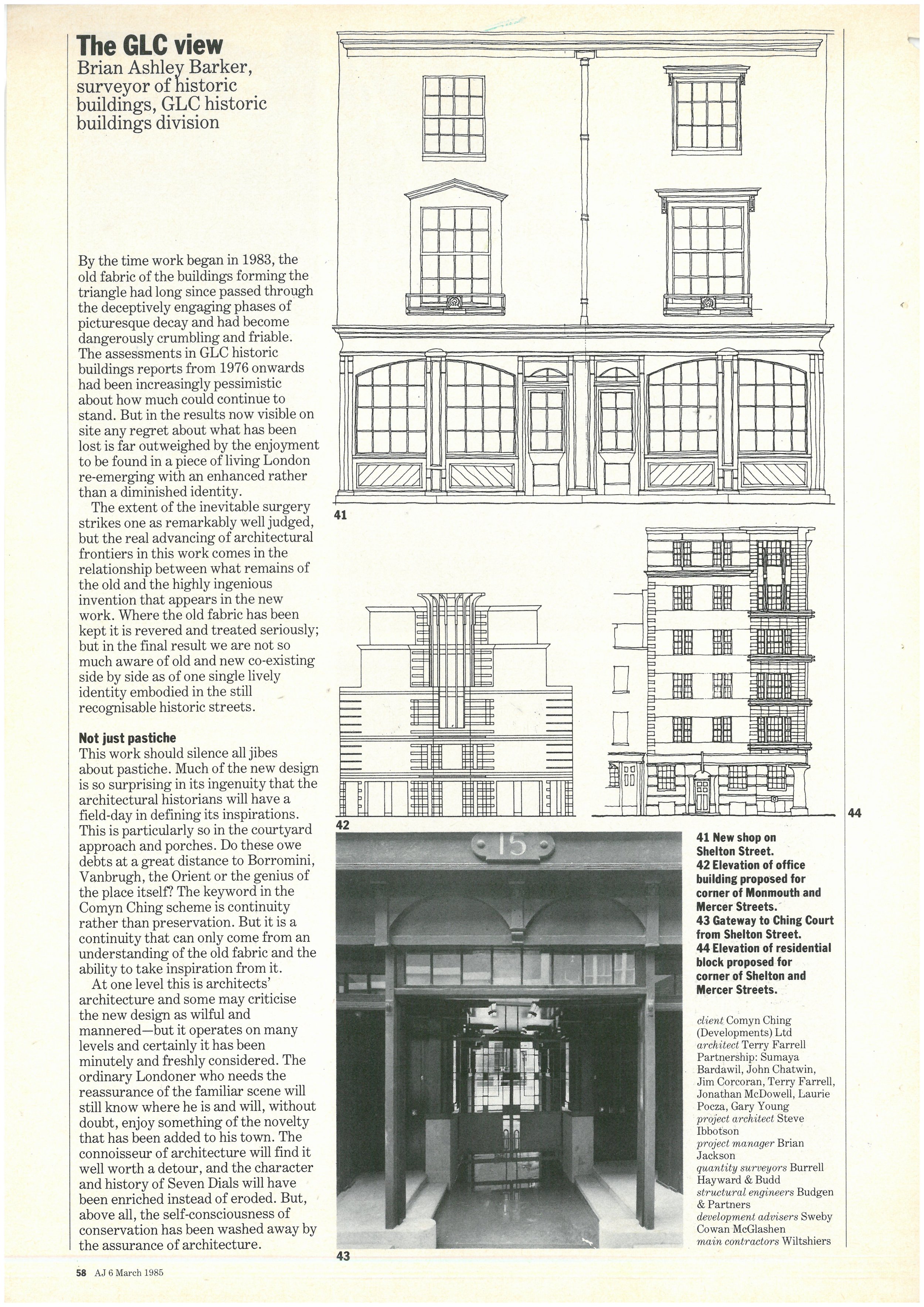

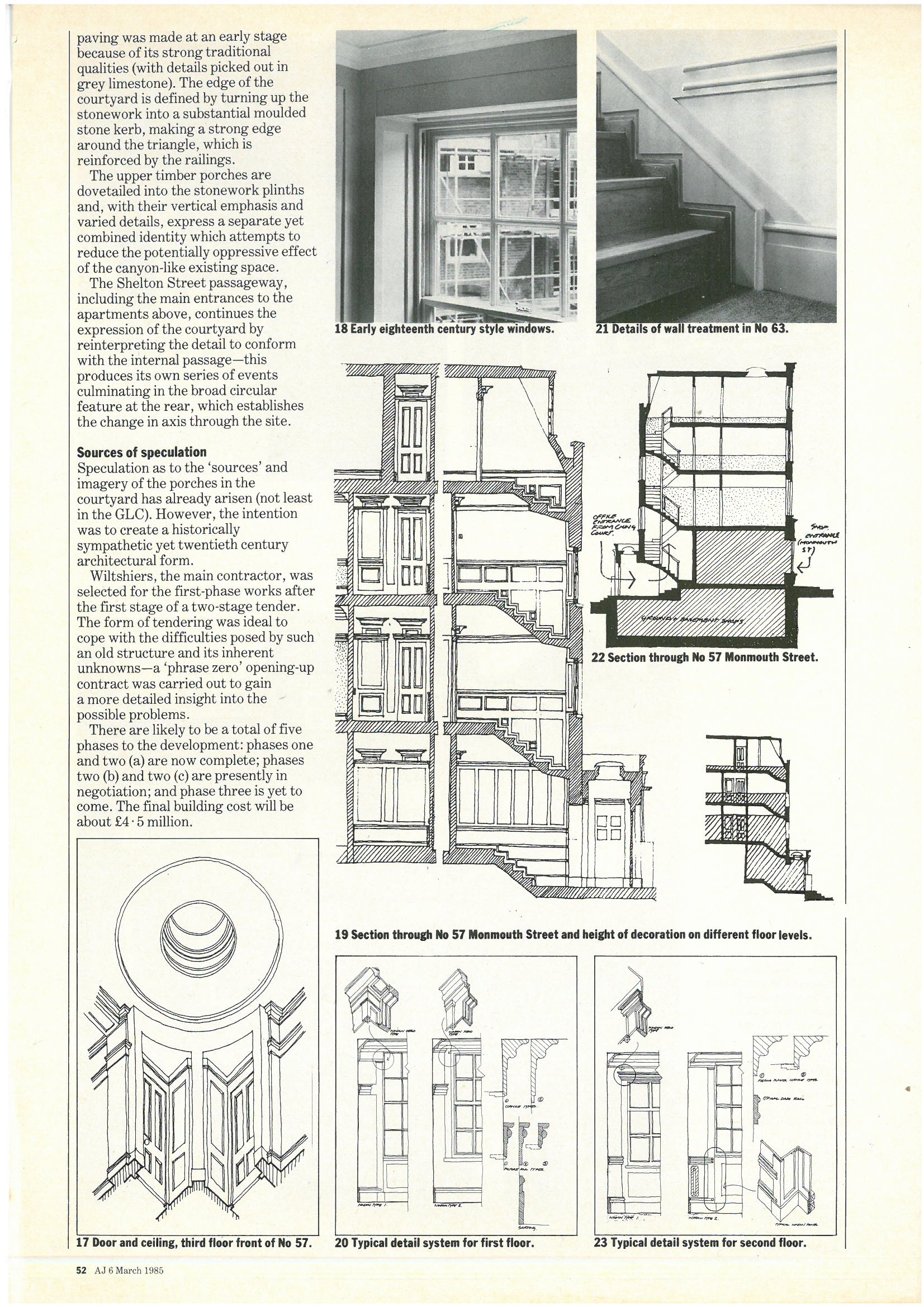

To provide a wider historical context for new interiors more studies were made of joinery from churches and state rooms from the period and earlier 17th century. These included the Jacobean interior stairs at Hatfield House built 1611, Sir Christopher Wren's churches, including St Anthony-by-the-wardrobe built 1695. New staircase balustrades were the first to be detailed. Following the cues from the Comyn Ching Triangle’s accurately restored originals, designs were created for new staircase balustrades and handrail profiles. An exaggerated scale of mouldings was introduced using references from joinery from the similar period. This experiment in scaling up the interior mouldings extended from stairs to rooms with cornice, dado and skirting mouldings. A traditional moulding was stripped of detail and exaggerated in scale to create unique designs for individual room proportions. Mouldings were cut in section as well as mitred to make explicit the larger and simpler cross section. A hierarchy of scale reflected the historic pattern of the restored houses with greater intensity in detail at first floor to reduced extent on upper floors. A list of the interiors is included in the submission to Historic England described below and illustrated in the Architects Journal feature on Comyn Ching Triangle 06 March 1985.

Design inspirations for the Comyn Ching Triangle courtyard

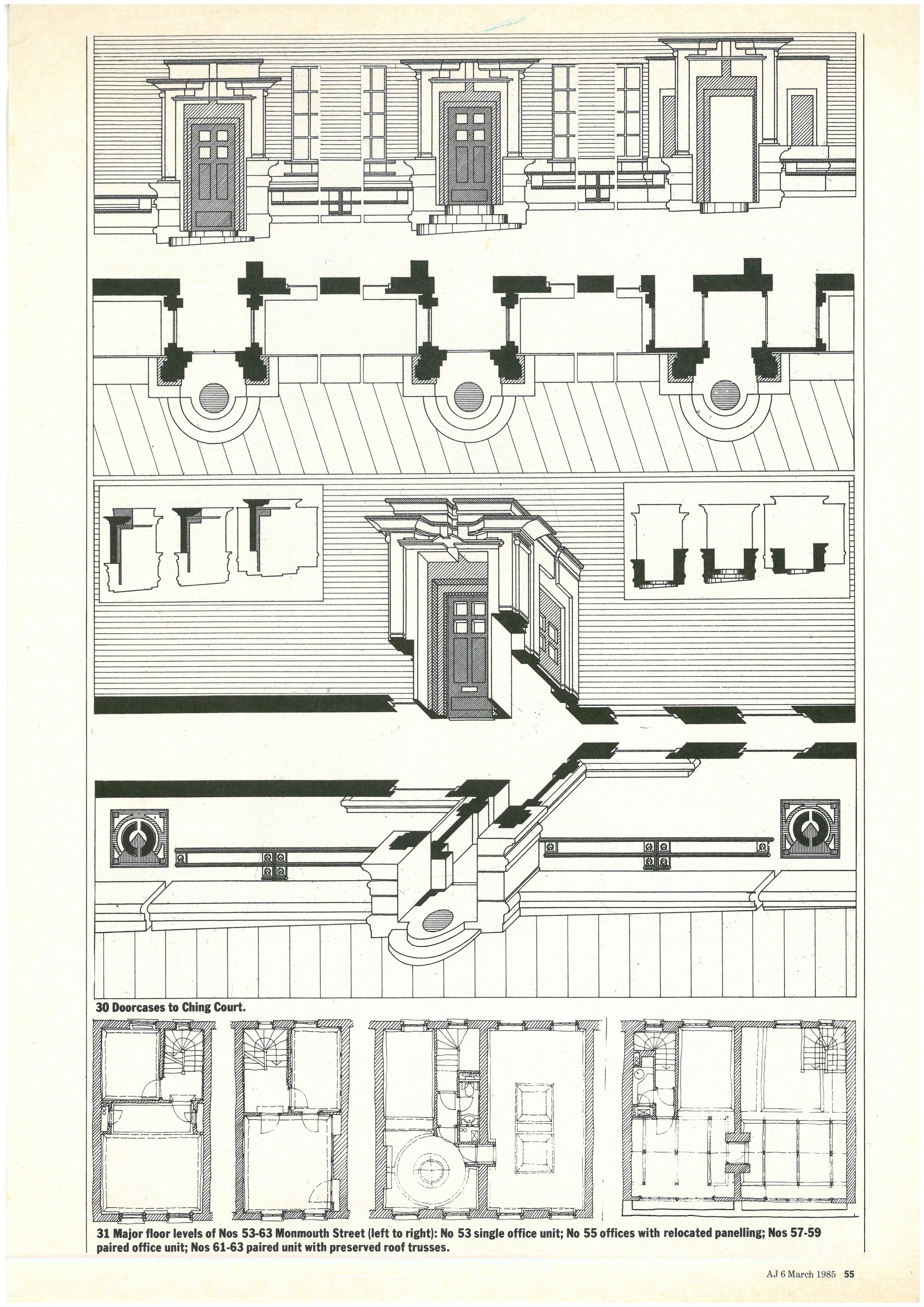

The new door cases and stonework designs in the Comyn Ching Triangle courtyard share a common architectural language and detailing with the new interiors of the renovated historic buildings. The same theme of simplified and enlarged scale detailing emphasising solidity and permanence gives the doorways a scale to fit their significance as entrances within the setting of the new courtyard.

The proportion, design, scale and detail of door surrounds had many influences which were refined through direct observation and sketching. These included the craftsmanship of timber shopfronts, door and window surrounds within and local to Comyn Ching Triangle. Early 17th century London buildings with baroque influence were studied such as the Orangery at Kensington Palace built 1704 by Hawksmoor and Vanbrugh. The exaggerated scale and cut moulding of stonework and timber in the courtyard was influenced by 20th century designs. The garden designs of Edwin Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll at The Deanery in Sonning built 1901 were inspiration for the paving and steps. Charles Rennie Mackintosh's Hill House built 1904 provided inspiration for the scale and detail of timber surrounds and ironwork. Stonework details from the 12th – 16th century Castle Acre priory in Norfolk were studied, along with the exaggerated scale, asymmetry and surprising level changes in James Stirling Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart built 1984 .

The composition, proportion and scale of the courtyard door cases evolved from a rapid, fluid and iterative design process, which elegantly took account and mastered the sloping courtyard. The door case locations and functions were dictated by the stair and door openings for entrances to the office floors above and required both single and paired entrances. The design for an assertive symmetrical single door in the centre of the group created the opportunity for the doors either side to respond with freer flowing detail and confident handling of asymmetry and level changes. The central door case has proportions of a period door case with timber surrounds and a stone plinth at chest height balanced equally at each side. Three external semi circular steps to the stone plinth create a well proportioned height and stature to this door case.

The sloping courtyard levels at the single entrance door to the south gave required fewer steps external to the door and more inside. This constraint was taken as an opportunity for variation with increased height for the timber door case surround using a double fascia. The stone plinth designed asymmetrically balances the height of the timber surround and accommodates the sloping external courtyard, with one plinth shorter and one much taller than human scale. This distortion alone could have been uncomfortable, however the intentions are made clear in combination in the third door case with a different asymmetry. The detail of stonework and timber are clearly resolved with elements of the group complementing each other.

The third door case to the north provided a single entrance with a pair of doors leading to two stairs and required minimal external steps. The central door case design was again adapted to include a pair of side wings slid back unequally behind the door case surround. The stone plinth is shorter on the left and taller than human scale on the right as transition to the scale of the larger corner building with a significantly larger flight of steps to the corner passage. The overall set of three door cases using complimentary elements with surprising distortions draws attention and provokes interest in their design, whilst creating a completely harmonious group in combination with the rest of the courtyard.

The passage and gateway into Ching Court from Shelton Street uses the proportions of the existing shopfront, with two narrow side doors and wider central opening. The detailing of the passage has similar elements to the courtyard stonework and timber doors, adding surprise and exaggerated scale with pilaster capitals of paired sections from the interior cornice mouldings. The passage height is compressed and exaggerated by the squat proportions, in direct contrast to the elevated scale and unconstrained height of the door cases within the courtyard. Rear windows in the courtyard elevation of the Shelton Street shops are framed in stone with receding size steps creating daylight and glimpses into the basement. The detailing of stone with rounded soft edges contrasts with the expressive stone cut sections of the door cases opposite. The larger window to the Comyn Ching shop has a three bay proportion and plainer detailed timber surrounds similar to the existing shopfront of the gateway.

Design Inspirations from Kensington Place Orangery by Hawksmoor; Gardens by Lutyens and Jekyll

Around the perimeter of the courtyard stone details provide a continuous skirting edge to the paving and a parapet for basement areas on two sides. This detail with an enlarged half round moulding links the door and window surrounds and forms a comfortable seat. The door case stone plinths have the round moulding cut in section which create a reference to the mouldings in the interiors. The third side of the courtyard provides a welcome resting place, a pause from the intensity, often used by local workers on sunny days. Two trees in circular tree rings are framed by a stone plinth around a timber Lutyens garden seat, with similar but subdued stone details and highlights in the form of cast iron motifs created specifically for the Comyn Ching Triangle.

The confined triangular courtyard and sloping floor create a surprising & diminishing perspective, a juxtaposition of exaggerated scale door cases, window surrounds, steps and copings creates a baroque tension between the human and monumental scale. The result is a magical courtyard space, complete and intimate at ground level, then soaring higher and appearing larger than expected. The observer wandering between the linked doors and stonework perceives in-the-round visual images, creating memories which are both harmonious and strikingly eye catching.

Comyn Ching Triangle inspiration for 2015 novel "Mime Order"

The Comyn Ching Triangle courtyard is a place of inspiration in the 2015 novel Mime Order by Samantha Shannon which sets Seven Dials in the future year 2059 "The courtyard at the back of the den is one of my favourite places in all of London: a triangle of tranquillity, paved with smooth white stone. Two small trees grew from circles of soil and Nadine kept the wrought iron planter boxes overflowing with flowers. Jaxon sat down on the bench and dropped his extinguished cigar into one of them. 'Do you know the rules of scrimmage Paige?'

http://theboneseason.wikia.com/wiki/The_Seven_Seals http://theboneseason.wikia.com/wiki/The_Mime_Order_(book)

2016 alterations to 73-75 Monmouth Street, 1-9 Shelton Street

The 2016 alterations to the facade of 73-75 Monmouth Street highlighted the need for each part of the group to be considered as a part of the whole Comyn Ching Triangle.

The south corner fronting St Martins Lane included a group of listed existing houses with a new build frontage "prow", which was not listed. The original approved uses were retail basement and ground floor, offices on first, second third and residential fourth (top floor). The 2016 proposal included the existing office use to be changed to residential and additional balconies and doors on the upper floors of the street facade.

The original design for the corner had glazing projecting in a three storey V shape, contrasted with a V shape recessed door on the residential top floor with projecting V shape canopies above at high level and below at entrance level. The projecting and recessed elements and triangular detail referred to both the design of the other two corners and the triangular courtyard.

The 2016 alterations removed the V shaped projecting and recessed glazing and the balcony ironwork with CC cast iron logos in a red contrast colour. These were replaced with some very ordinary square fronted balconies and flat glazed doors. Whilst this diminished the streetscape, the majority of the original design was unaltered and is now protected by the listing, retaining the architectural significance and relationship to the whole concept running through the Comyn Ching Triangle.

Comyn Ching Triangle – description submitted to Historic England by Gary Young 01-06-16

Interiors of historic and architectural interest:

The interiors of terrace 55-63 Monmouth St contain originally listed interiors on upper floors and connecting by the listed staircase to doorcases from Ching Court.

55 has original reinstated restored and listed timber wall panelling in the first floor and staircase which was relocated from 49 Monmouth St.

53 to 63 Monmouth St upper floors are office interiors including parts of original staircases which were restored. New interior panelling, mouldings and stair details on 53, 57, 61 and 63 on first to third floor were inspired by the originals found at the site and detailed in a style also similar to the external doorcases. Ironmongery was all supplied from Comyn Ching.

The interiors of the shop at 19 Shelton St was designed for Comyn Ching may be of interest - although may have changed with new tenants.

The flats 11-19 on upper floors were more simply decorated than Monmouth St offices, with limited amount of mouldings and colours matching Monmouth St interiors. Ironmongery was all supplied from Comyn Ching.

Comyn Ching Triangle description submitted to Historic England by Gary Young 15-02-16

Historical interest

The Comyn Ching Triangle at Seven Dials, Covent Garden, is one of a number of triangular blocks created when Sir Thomas Neale laid out Seven Dials in 1692. This block has retained many original buildings, and is a significant part of this early example of urban planning in London.

The Comyn Ching name originated from the family names of the Cornish and Northumbrian founders of the ironmongery business established in Seven Dials during the early 18th century. The company flourished and accumulated properties opening a shop on Shelton Street in the early 18th century. By expanding into the rear yards to create more storage and then along the street fronts they created a labyrinth of workshops and stores. By 1978 Comyn Ching owned the entire block bounded by Monmouth St, Shelton St, Mercer St, and finding difficulties with the antiquated storage and repair of the now listed group of building, the company moved their entire business into new buildings in Holborn.

Architectural design strategy

Comyn Ching commissioned Sir Terry Farrell’s practice in 1978 to produce a regeneration strategy, in consultation with GLC historic buildings division, for repair of the existing fabric of the listed houses and a masterplan for new uses which would make the repairs viable. The repair strategy continuing through 1978-1983 was two stages, firstly as an overall strategy to define and agree the historic and architectural merits of what should be kept and repaired and what could be demolished and rebuilt new. Then secondly consultation and detailed consents for methods of repair, reuse and reinstatement of listed fabric with interventions to create usable floor space and safety standards. The concept to create a new courtyard and three new corner building was established during this strategic stage 1978 to 1980, creating s the new identity and context for the retained listed buildings and allowing flexibility for mixed use. The scheme progressed in a phased way, with Comyn Ching being the client for the regeneration of the courtyard and the listed houses and occupying a shop unit for their own showroom, whilst the corners were to be sold to developers for mixed uses, which provided the funding for the necessary higher costs for the listed building repairs.

Ching Court

The interest continues into the courtyard where each of three corner building contributes to part of the courtyard elevation, presenting variations on the cylindrical and triangular primary forms as projecting or recessed balconies and bay windows. A design tour de force, the courtyards restored and new elevations, new door cases stonework and railings with contemporary ironwork motifs derived from Comyn Ching’s historic metalwork logo. Variations on the design theme in the new corners are continued through into the courtyard paving, railings and gates.

The detail of the Comyn Ching Triangle and Court relates to the Georgian scale and contemporary scale of the new parts of the group, expressed knowingly in the elevation proportions through the detail highlights between projecting and recessed elements, brick in contrasting bands and black balcony ironwork with CC logos in cast iron with a red contrast colour.

Architectural Significance

The development has been cited by historians and architects as an exemplar urban regeneration winning a Civic trust Award in 1985. Brian Ashley Barker surveyor of historic buildings, GLC historic buildings division, stated in the Architects Journal 06th March 1985: “Where the old fabric has been kept it has been revered and treated seriously; but in the final result we are not so much aware of old and new co-existing side by side as of one single lively identity embodied in the still recognisable historic streets”.

The architectural and historic significance lies in the overall approach, with new design creates a group value where the individual parts of go together to make a whole which is greater than any one part, but all are entirely reliant on each other. Examples of this approach include: details in the new courtyard door frames inspired by restored historic shopfronts and sharing details with new building entrances and articulation of facades; the unique cast iron logos based on the historic double C motif of Comyn Ching, used in railings on the courtyard and throughout balconies on buildings; the scale and proportion of new buildings on corners reflecting both the considered proportions, detailing and materials of the 18th century houses, as well as the urban context and grouping of adjacent Victorian and 20th century buildings.

Concept for mixed use development

The development designed by Terry Farrell Partnership from 1978-1988 comprised the restoration of the group of 25 retained listed early 18th century houses above shops in three terraces, including Comyn Ching’s own shop at 17-19 Shelton Street and creation of a new public space Ching Court in the middle of the triangular block. Three new infill buildings created at the corners for mixed use, replaced poorer quality 19th century buildings and all three responded to different contexts but share similarity in design approach.

The three corners of the Comyn Ching Triangle are designed to complement each other; each being different but connected to the whole. The designed assemblage inspired by Colin Rowe’s “Collage City” published during the early stage of the design, by Sir Terry Farrell is regarded as one of the best examples in the UK of the Post Modern approach to urban design and architecture.

Phasing and programme

Enabling phase –design commenced 1978 - start on site 1981- completed 1983

Listed building consent and demolition of corner buildings at Seven Dials plus removal and storage of late 17th early 18th century panelled interiors and stairs from 49 Monmouth St for reinstatement in 55 Monmouth Street during phase 1.

Phase 1 – start on site June 1983- completed May 1985

Restoration of 15 listed late 17th early 18th century houses for conversion, restoration of shopfronts and creation of Ching Court and new entrances to upper floors. These Ching Court listed houses dated from late 17th and early 18th century. 53-55 Monmouth St and 21-25 Mercer St, clearly evident from the elevations roofs and sash windows, were pre 1707-9 Building Acts and others with recessed windows and parapets were post 1709 - possibly rebuilt elevations onto older houses. Existing panelling which was relocated from 49 Monmouth St was restored in 55 Monmouth St. Rich with historical and architectural interest - original elevations, interiors and detailing covered an innovative period of 40 years from 1690,s to 1730's matched by new interiors and door case and stone work detailing designed in 20th century within the spirit of the group.

53-63 Monmouth St was converted for a mix of offices on three storeys, above retail ground and basement,

11-19 Shelton St converted for mix of flats on three storeys above retail ground and basement

21-27 Mercers St converted for four private sale houses

Phase 2 – start on site 1985 – completed approx. 1987

New build on Seven Dials for four storeys of offices above ground and basement retail at 45- 49 Monmouth Street& 29-31 Mercers Street.

New build at 19 Mercers Street, 21 Shelton Street for flats on six storeys plus basement.

Phase 3 – start on site approx. 1989 – completed approx. 1991

Restoration of 4 listed and 4 unlisted 18th century houses and shopfronts with new build bookend for residential top floor, offices on three storeys, above retail ground and basement.

New corner buildings

Seven Dials office and retail corner building; 45- 49 Monmouth Street, 29-31 Mercers Street

At Seven Dials the office building brick facade relates to the height and proportion of adjacent historic houses, then steps up through layers of patterned brick to a set-back top storey, reflecting the height and complexity of the commercial buildings opposite. The corner has a glazed cylinder coloured in contrasting dark red, which is part engaged into the stepped brick facade and part projecting to culminate in a circular form as a dynamic feature for the open space at Seven Dials.

Residential corner building 19 Mercers Street, 21 Shelton Street

The building at the corner of Mercer and Shelton Street repeats the patterned brickwork and set back attic top storey from Seven Dials, using the cylinder form and colour in the framing to the corner bay windows. The Mercers St building is viewed within a much tighter, rectilinear streetscape, therefore projecting cornices and contrast colour bricks are introduced to mark the building as part of the Comyn Ching group assemblage.

Mixed use corner building facing south to St Martins Lane - 73-75 Monmouth Street, 1-9 Shelton Street

The corner facing towards St Martins Lane at the acute junction of Monmouth Street and Shelton Street repeats the brick pattern and colour contrast, adding a triangular form derived from the whole block, expressed in the V shape projecting glazing. The push pull theme of the primary forms in other corners is repeated with contrasting projecting bay and V shape recess on the top floor. Projecting cornices at high level and canopies above the entrance repeat forms from Mercer St. This corner building is closely attached to the restored 18th century terraced houses and tales reference both to their scale and detailing and to the other corners, making this corner a key part of the group assemblage.